An argument in concrete: a history of Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre

The Crucible Theatre in Sheffield is home to one of the most exciting performance spaces on the planet. Its huge thrust stage imposes its will on even the giants of world drama, and in the right hands, the results can be spectacular. It can also do strange things to the people who go there… as we’ll see in this personal history of the theatre and its curious allure. And I should mention: this article is a defiantly snooker-free zone.

I look immaculate in cheap clothes and hair gel.

Black polyester trousers, sharply creased; a clean white shirt a little thinner than is comfortable; a maroon waistcoat, its man-made fibres firing off static as I walk; and a matching bow tie fastened with Velcro round my neck. And at this time – it is the back end of 1989 – the Air Wair sole is my shoe tread of choice, so every step I take is like a trampoline bounce across the floor. My feet are oil resistant, acid resistant, ready for hard labour. Or, indeed, for a night in the theatre, which is precisely what they have in store.

This is the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield, and I am about to begin work for the evening. I am the Theatre Fireman, which sounds grand, though I am really no more than an usher with a fire safety certificate to my name.

I emerge from the tiny men’s changing room that’s jammed into a vacant corner just out of reach of the public, and I step through the pass door near the top end of the bar. And once through it, the Crucible’s brutalist canyon stretches away in front of me – its foyers, its kiosk, its coffee shop, its carpet. It is both gaudy and austere; white walls, cryptic arrows, wide expanses, stainless steel. A carnival of clashing primary colours covers the floor beneath my feet. Sometimes this place can bustle, but at just turned half past six, the air hangs still. There is a sense of early evening torpor, of an event that has not yet begun.

I scoot round the gents’ by the fag machine and check everything is in order. No taps left running, no kids mucking about. Back into the bar I go, then down the fire escape stairs to the basement where I throw open the doors to ensure that evacuation routes remain unobstructed. Having satisfied myself that the way is clear, I close the doors again and saunter along the lower corridor, past workshops and wardrobes and props stores, breathing deeply the scent of resin and wood. Every fire extinguisher I pass is inspected: are its pressure gauges satisfactory?; is its location correct? If I find one propping open a fire door, I tut-tut to myself and lug it back into its proper position. Then I hurry on; and round the corner; and I head into the void beneath the stage.

Each time I arrive here, I hope that I will be alone. Punching open a set of double doors I plunge into the chasm that gapes before me, and I wallow in the semi-darkness as if on a trip to a Castleton cave. I love it down here; it feels electric. It’s where the mysterious energy of theatrical creation collects after the evening is over: I feel it prickling at my skin as I move.

From production to production it changes. It can be a vacant space, like a multi-storey car park at midnight; a place for the handing over of secrets or brown envelopes wadded with cash. Or it can be densely forested with hydraulic lifts, props, the undersides of trapdoors – a deceit of theatrical trickery exposed from the inside. There are more fire extinguishers to check; more potential escape routes to clear; but as I carry out my duties I’m careful to watch my step. Because here are buried dead salesmen and wicked witches; a Yorick, and Captain Hook.

I am allowed to be here; it’s in the job description. But at the same time I feel nervous of being found out. I imagine that should some assistant stage manager find me here, they will recognise my excitement as being something not entirely… professional; I think they will sense my undisguisable thrill, and realise that my journey through this mystical cave is more about my personal pleasure than about checking that fire exits meet the statutory regulations. That’s why if anyone finds me here, I will feel guilty, and I might even run.

So with a fear of imminent discovery travelling with me, I creep onwards; the plywood boards of the Crucible’s stage are just a little distance above my head. I reach one of the two steeply-ramped tunnels that lead from below ground up onto the forestage, emerging amid the banks of seating deep within the auditorium. And trudging up the ramp – my heart not exactly in my mouth, but definitely not where it is supposed to be – I catch my breath as I step out in front of a non-existent crowd.

I am live on stage at the Crucible Theatre, Sheffield; but there is no one with whom to share the moment, because here I am, standing alone.

—

Opened in 1971 under the artistic direction of Colin George, the Crucible Theatre replaced the small though well regarded Sheffield Playhouse on Townhead Street, home of the Sheffield Repertory Company, which had presented a succession of classics down the years, often featuring soon-to-be-household names such as Paul Eddington, Patrick McGoohan and Nigel Hawthorne. The Rep’s programme was based on a fortnightly production turnaround, and benefited from an audience packed with subscribing regulars: they would have the same seat booked throughout the season, returning every fortnight to see whatever there was to see. It could be Shakespeare, or Toad of Toad Hall, or Harold Pinter; no matter what the play was, their custom could be relied on to keep the company flush with air kisses and grease paint.

Repertory companies of this type were a mainstay of twentieth century British theatre beyond London. In Sheffield, Liverpool, Birmingham and elsewhere, groups of theatrical professionals were powering their way through a succession of reliable classics, rehearsing one show while performing another, sharing out roles, mastering their trade and building a local audience that trusted them not to push things too far. With enough of this trust in the bank, the rep companies could dare to perform new work that they felt to be important, rather than relying on well-worn titles with which their audience would feel comfortable – hence, the likes of John Osborne and Arnold Wesker could occasionally get a look in. But it was a balancing act, and one that was important to get right. These companies were not publicly subsidised, and challenging their audience to the point of alienation was not an option that was open to them. The context in which they existed necessarily limited the scope of their ambition.

The rep company world, however, was not sealed. The young actors and directors for whom it represented the bread and butter of their trade were nevertheless connected to a theatre that was changing, and those socially-charged new writers and emerging European influences of the 1950s and 1960s were hard to resist. There was a sense that those who created the energy that helped the best rep companies burn brightly wanted to go further than their circumstances would allow.

They wanted a degree of freedom from the tyranny of the box office and acknowledgement of the right to fail in pursuit of work that was thrilling and new. They wanted to establish theatre-in-education companies and build links with their communities – the whole community if they could, rather than simply those who already came along week in, week out. Not only did they want to transform the work they were doing on stage, they also wanted to develop everything that went beyond the demands of the productions that kept well-upholstered behinds on the same cosy seats. And they wanted to throw open their doors in the morning and welcome in shop assistants, gas fitters, teachers and bricklayers, families with children and those who just wanted to get out of the rain; for coffee, for a meal, for a chat, and – who knows? – maybe even to see a play!

The combination of new public funding and visionary artistic endeavours would probably have been enough to transform the productions and usher in a new age of education and community work – the Liverpool Everyman, for example, became one of the most socially-engaged theatres in the country while operating in the most sub-standard of surroundings – but to achieve those democratic buildings which might become places of secular communion in the heart of the city, something else was required: new construction. The fabric of the existing modest little playhouses did not seem to allow for such inclusive dawn-to-dusk operation, but public money, post-war redevelopment and not a little intercity one-upmanship were destined to change everything.

With Blitz-scarred cities already planning grand new precincts, transport schemes, housing projects and cultural landmarks, there were opportunities for the rep companies to stake a claim in the future. They pressed home the point that a dynamic theatre should be an essential feature of a civilised city, like parks and transport and someone to empty the dustbin; and this theatre shouldn’t be economically reliant on the same old faces, but should be supported by the government and the city itself. It was an argument that was won – for the time being – and one by one the rep companies stopped making do and mending, and moved into brand new homes fit for what they hoped would be a distinctly more daring existence.

The Belgrade Theatre in Coventry was the first of the post-war British theatres. Opened in 1958, its Festival of Britain frontage merged seamlessly with the brand new brick and concrete of its surroundings, and its timber-lined auditorium radiated a natural warmth that was a world away from the shadowy nooks and crannies of older theatres. In an era of demolition, those dark crusty playhouses seemed to invoke the guttering gas lamps of Victorian melodrama, and were thus – more often than not – swept away. By contrast, the Belgrade Theatre’s wide open proscenium arch was ready to frame the works of a more inclusive age.

Except…

Proscenium arches. Picture-book illusions. Rooms within rooms.

Was the Belgrade, with its stalls and its balcony and its traditional picture-frame presentation, really ready to usher in a brave new world? In conception, maybe it was, but in its internal arrangements, it was far from revolutionary. Clearly, there was still a lot further to go.

The hovering concrete slabs of Nottingham Playhouse followed in 1963, again with a proscenium arch, but one which could be adapted with a peninsula that projected forward. As far as its architect, Peter Moro, was concerned, a self-conscious connection between actors and audience was being made, as he explained to the BBC in December ’63:

“I have tried to make a proscenium theatre where this link is established and where there’s no barrier between the actor and the audience.”

By the late 1960s, there were new theatres pending in Birmingham, Leicester and Derby, the latter two both blooming as the cultural branch of an integrated shopping centre seemingly descended from the genus Arndale. There was the National Theatre in London which, having long harboured a wish for some prince-baiting concrete of its own, finally began construction on the South Bank in 1969. And then, of course, there was the Crucible. Because it was inevitable that in this climate, the Sheffield Repertory Company with its cramped little playhouse, and the Sheffield Corporation with its need to turn wartime bomb sites into grey breezeblock landmarks that could stand comparison with – or even surpass! – the grey breezeblock landmarks being laid anywhere across the north, would concoct a plan to build a new theatre of their own.

—

Talking to the Theatre Archive Project in 2005, Colin George – who became artistic director of the Sheffield Playhouse in 1965 and who led the new theatre project through to completion – explained the city council’s noble artistic urge:

“They said ‘We want to build a new theatre’, because Leeds is getting one, Nottingham’s got one, Belgrade Coventry… everybody’s got to be in! They felt Sheffield was missing out.”

Well, perhaps the urge was not so noble after all. However, while the ladies and gentlemen of the Corporation may have been fired by envy, at least their competitive frenzy seemed to favour a spirit of adventure, and they were minded to listen when Colin George explained what he had been imagining – a theatre in which actors and audience shared the same space. It was the way his company performed for children in schools – in a semi-circle – and it changed the nature of the work, helping it become three dimensional and dynamic in a way that the picture-frame form could never be.

So they listened to him, and perhaps they understood; or more likely, they did not. But fortunately, Colin George was not the only voice to speak up for a new approach.

Enter… Sir Tyrone Guthrie.

Guthrie was an actor, a director, a visionary, a giant. Born in 1900, he had been in the theatre for decades; he had run prestigious companies and travelled the world, and in 1948 he had presented a play in Edinburgh that had crystallised his ideas for a new theatre – though one with historical antecedents. His production of The Thrie Estaites had taken place in the Church of Scotland Assembly Hall, where an open raised platform was surrounded by seating on three sides. To anyone with a passing knowledge of theatre history – and to Guthrie most certainly – it brought to mind not only the projecting stages of the Elizabethan age but also, harking back thousands of years, the ancient theatres of Greece. Still, in the context of most people’s experiences of mid-twentieth century theatre, this was something thrillingly fresh.

“One of the most pleasing effects of the performance,” wrote Guthrie in his autobiography A Life in the Theatre, “was the physical relation of the audience to the stage. The audience did not look at the actors against a background of pictorial and illusionary scenery. Seated around three sides of the stage, they focused upon the actors in the brightly lit acting area, but the background was of the dimly lit rows of people similarly focussed on the actors.”

Guthrie was gripped by the possibilities that this re-acquaintance with an old form had opened up. With little scenery, but with a startling proximity between the actors and their audience, the stage could be filled with vigour, colour and movement; this was the type of stage for which the Elizabethan classics were written, and on it, they came alive.

Four years later, Guthrie had an opportunity to develop his ideas when he was invited to work with the Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Ontario. Their theatre was yet to be built, and under the guidance of Guthrie in collaboration with the designer Tanya Moiseiwitsch, a large concrete amphitheatre with a central thrust stage was conceived and created. Initially surrounded by a temporary tent for its first performances in 1953, it quickly became an acclaimed and successful new space, and by 1957 the stage had been enclosed in a permanent building – the Shakespeare Festival Theatre.

By the early 1960s, Guthrie and Moiseiwitsch were able to experiment even further, this time in the planning of the Tyrone Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis. They yanked at their basic design, creating an asymmetrical thrust stage that, viewed in plan, seemed to lurch off to stage right, perhaps pushed by some unseen force. The result was an auditorium with a diagonal energy; it seemed designed to force the hand of the directors who worked there, insisting that they conceived their production in terms of the movement across the stage, mitigating against the creation of pretty symmetrical pictures that looked nice from the centre seats but that wouldn’t work for those sitting elsewhere.

In Britain, the Chichester Festival Theatre opened in 1963, again with a full thrust stage that was influenced by Guthrie’s ideas, although it was built without his involvement. It was a remarkable achievement, being established without public subsidy and therefore standing outside the ranks of the new local authority-backed theatres, but the great man had misgivings about its design; specifically, he felt that the rake of its auditorium wasn’t steep enough. This reduced the intense focus on the stage.

Then in 1967, Guthrie met Colin George in Sheffield; he was speaking at a meeting to raise funds for the city’s as-yet-undesigned new theatre, and he asked George what type of building he had in mind. “We’re trying to get out into the audience,” replied George, which for Guthrie, was no doubt his starter for ten. He said they should consider a thrust stage, and within a week, Colin George was travelling to Ontario and Minnesota to visit the existing Guthrie theatres for himself.

And he wanted one.

—

So the new theatre in Sheffield became the next great project of Tyrone Guthrie and Tanya Moiseiwitsch; they worked together with Colin George and his Sheffield Repertory Company, the architects Renton Howard Wood Levin, and the gruff local men of business and politics who just wanted to go one better than Leeds. It was to be a theatre in the spirit of the times – open and democratic, iconoclastic, forward thinking. It could be argued that it was also in the spirit of Sheffield itself, breaking new ground in a radical city that was building a particular brand of municipal socialism.

But…

For every idealistic South Yorkshire revolutionary, there was a stick-in-the-mud or ten who knew what they liked and liked what they knew, and what they liked was a theatre that looked like a theatre. For starters, a curtain wouldn’t have gone amiss. With the familiar old Playhouse set to close, and a pile of bricks where the spectacular Sheffield Empire had stood, and even the stately Lyceum closing its doors in 1969 – the same year they broke ground on the Crucible’s new site – Sheffield seemed to have lost its ‘traditional’ theatres for ever. And while thoughts of thrust stages might have sent shameful shivers through the loins of men wearing make-up and tights, there were many in the press and on the street who were happy to consign the new theatre to history before the concrete had even been poured.

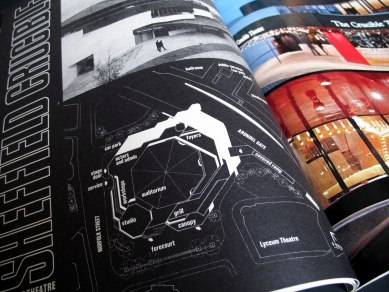

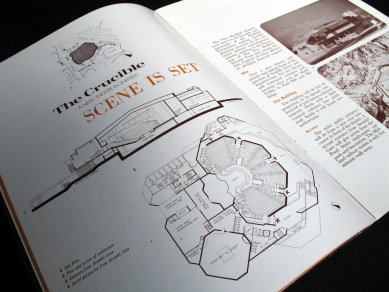

Because of course, this theatre wouldn’t have a curtain; it would be a refinement of the Guthrie creations in North America. This time, Tanya Moiseiwitsch based her design on an octagonal plan with the stage at its centre. The auditorium and rear stage area followed the octagonal scheme, a pattern which was then taken up by the theatre’s architects and implemented throughout the rest of the building.

As with the theatres in Stratford and Minneapolis, the central performing area was a raised promontory that stepped down to a ‘moat’ dividing the acting space from the audience. The 1000 seats swept around the stage in a steeply-raked semi-circle – though one that again hugged the five foremost edges of the octagon, while two ramped tunnels – or vomitoria – enabled actors to be spewed onto the stage from within the theatre’s hidden depths. At the back of the stage stood five moveable towers that could be clad in a variety of materials according to production requirements, and which featured ladders and balconies for a range of entrances and effects.

But tennis racquets and French windows?

There weren’t any.

In choosing a thrust stage theatre, and gifting it a prime piece of land, and building it from scratch while the citizens chuntered on, the theatre’s backers and supporters were making a brave decision, and an ideological one. In fact, they were making an argument in concrete and glass. Theatre could be different they were saying; times had changed; let’s move on. The proscenium arch theatres that people were used to were not the last word; they were good at some things, less so at others; so why don’t we try something new? Television was the chief reason that so many old theatres were closing, and by accident, the rigid picture-frame arch had become a poor mimic of the box in the living room. This new theatre then could be the anti-TV, theatre’s saviour!

It wasn’t as though there weren’t alternatives. They could have had their new theatre, their glass and their concrete, but with a stage that was less of a statement. Or they could have saved the Victorian Lyceum, renovating it and rebuilding where necessary so that the new could be overlaid on the old. There was no doubt that Sheffield would have liked that. But for a city that was sweeping away slums and stacking new housing towards heaven, that was replacing its grammar schools with comprehensives faster than anywhere in the land, that was trying to deliver a subterranean new Eden for pedestrians and wide open boulevards for cars, it would have been some kind of defeat.

With no other professional theatres within miles, Sheffield really was throwing all its theatrical eggs into one octagonal basket. But it was a decision that was entirely of its time; and it was right.

—

Fortunately, the new theatre had friends. No doubt many councillors had misgivings, but the ones who had access to the cash remained resolute, and for now, they were the ones who mattered. The Arts Council too gave their backing; indeed the project couldn’t happen without them. And the begging bowl was passed around widely, among industrialists and philanthropists and anyone who had money to spare. Tony Hampton, who was chairman of the theatre’s board, explained to the Theatre Archive Project in 2003:

“There was nothing negative in the theatre at all, everybody was absolutely committed. We’d got the money, the Corporation didn’t interfere at all… and the Arts Council didn’t interfere. I had to raise this money but fortunately I’d been Master Cutler just before then so I knew all the people in Sheffield who had got any money.”

In 1969, the estimated cost of the entire project was £910,000, with a third to be raised from the public. Well-wishers could buy a brick for ten shillings, or have their name inscribed on a seat for £25, and a gift of £50 or more would give them priority booking for life (though having worked in the box office myself around 25 years later, I can only imagine the confusion that would have arisen had someone arrived at the counter and claimed this historic right).

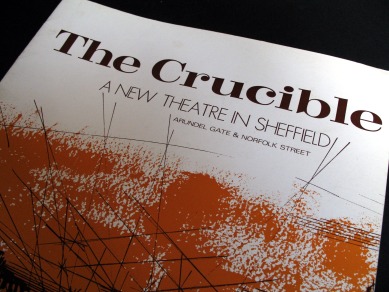

But rattling tins on the theatre’s behalf wasn’t enough: people needed educating about what the thrust stage would give them; they needed convincing that it was something they might want. So the leaflets had to be part propaganda:

“Theatre reacts to the other arts as it does to life around it,” claimed one brochure. “As painting did to photography, theatre has reacted to television and the cinema, and it has realised that one quality it has and the others lack is that of personal contact between actor and audience. It is three-dimensional in a way the others can never be. Sheffield is about to become a forerunner in this exciting development of the British theatre. When the new Sheffield theatre is complete it will have no equal.”

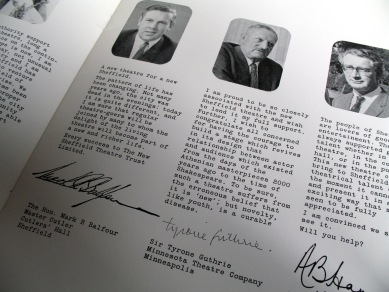

Sir Tyrone Guthrie himself spoke up for the project in a characteristically robust manner:

“I am proud to be so closely associated with the new Sheffield theatre,” he wrote, “and wish to lend it my full support. Further, I wish to congratulate all concerned for having the courage to build a stage which revives in its design that relationship between actor and audience which existed from the days of the Athenian masterpieces 2000 years ago to the time of Shakespeare. To be sure, such a theatre suffers from the erroneous belief that it is ‘new’; but novelty, like youth, is a curable disease.”

And again, in the same document, the message was hammered home:

“Theatre thrives on change. It never has been, nor if it is to survive will it ever be, undeviating and doctrinaire. Sheffield now has the chance to act as pacemaker to a new development. An opportunity it is grasping with both hands.”

<Choke back tears. Salute Vulcan. Invoke the name of Bobby Knutt.>

—

The name, then; what would the new theatre be called?

If the project’s first stroke of genius was a contentious one – being the form of the auditorium itself – its second inspired moment was rather easier for Sheffielders to warm to. In choosing ‘the Crucible’ as a name, not only did the theatre make the obvious allusion to the ‘melting pot’ of ideas that it aimed to become, but it also forged a bond with Sheffield’s specific history as the centre of British steel making and the eighteenth century innovation that propelled it forwards.

In the 1740s, Benjamin Huntsman of Handsworth perfected the ‘crucible’ steel process that meant a high quality product could be produced in great quantities: it not only guaranteed the future wealth of the city, but it also meant that one day, at the dawning of the far-off 1970s, Sheffield wouldn’t have to call its radical new theatre ‘The Octagonal Playhouse’ or some such. It would have a memorable name, an appropriate name; a name that can raise goose bumps of pleasurable recognition down the arm of your average Sheffield citizen, given that we all learn about Benjamin Huntsman over our first Farley’s Rusk lunch.

—

And so… the opening night approached.

The old Sheffield Playhouse was set to close in July 1971 with a rousing new musical; then a one-off gala night would launch the Crucible in November; then the first full production would follow, and what a treat it would be: The House of Atreus by Aeschylus, directed by Tyrone Guthrie himself. After all, he had been working on thrust stages for over 20 years; he had yearned for them, created them, and perfected them. So who better to take this stage and weave magic? Not in Canada, not America, but here?

But alas, it wouldn’t happen that way.

After his last dress rehearsal at the Playhouse, Colin George received the news that turned all kinds of things into what-ifs and might-have-beens. As he described to the Theatre Archive Project in 2005:

“The stage manager was hovering around and I thought, ‘Ah yes, the wigs haven’t arrived or something’, and he said, ‘I just thought you ought to know I heard on the radio that Tyrone Guthrie died this morning’.”

So that was that. Guthrie would not see the completion of the building he had nurtured as perhaps the ultimate expression of his particular view of theatrical presentation – the one that the Architectural Review called “undoubtedly the best theatre to evolve from the original Assembly Hall experiment”. And neither would the Crucible itself benefit from his decades of experience, his intimate knowledge of the thrust stage and how best to use it. Because unfortunately, this expensive new toy didn’t come with a manual. Colin George and everyone else who worked there would just have to write the rules for themselves.

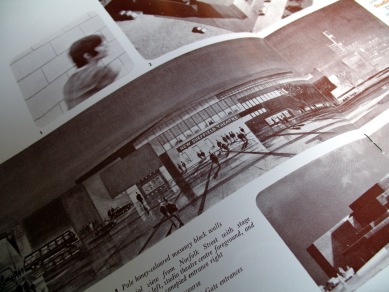

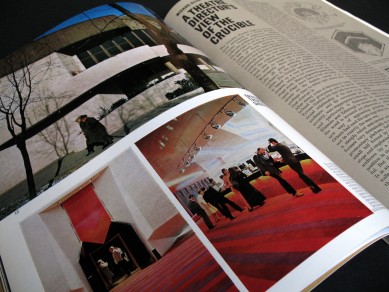

The first night gala was called Fanfare – a three-part programme designed to show off the new facilities in front of Sheffield’s great and good, who crammed the cavernous foyers with their flared evening suits, their Don Revie sideburns, their Mappin & Webb jewellery and their smouldering Park Drives.

As they approached the Crucible from across Tudor Place, skirting the car park where the Theatre Royal had once stood and casting glances at the silent Lyceum, they were met by an angular, squat frontage of white concrete blocks, like a cheesecake cut through with a knife. A lid of rich chocolate brown sat on top, while another dark strip jutted out from the front, roofing the entrance lobby and resting on a slender steel pillar. Row upon row of small bulbs lit the lobby like a dressing room mirror, and deep beyond the entrance could be glimpsed slabs of raw concrete, soaring walls, epic spaces; and flashes of colour, and the sheen of thick gloss.

Once inside, the space was enormous. It loomed upwards – to the main foyer via the most vivid of carpets; and it tipped forwards, down a graceful staircase towards the box office and kiosk. Everywhere was light and inviting and glamorous – in a modern way, a seventies way. Those people who climbed those stairs might feel that this was a theatre that Hockney would paint, or that Kubrick would put in a film. It was a theatre for now and tomorrow… or so it was hoped.

Sheets of dark glass gave views across the dual carriageway to the Fiesta, the Top Rank, the complexes and subways and ring roads that the self-styled ‘city on the move’ was so proud of. And beyond them, the flats at Park Hill; another civic endeavour for a science-fiction future. All these things were still in their gleaming prime; they were first drafts of the world yet to come, and this, it seemed, was the new world’s opening night.

So they swilled their pints of Double Diamond and they took another high-tar drag, and they shuffled towards the auditorium wondering what on earth it was going to be like. Five doors gave access to the theatre’s interior, all tall and deep black; and above each one flew an enormous coloured arrow that directed the patrons to their allocated part of the house; according to their ticket, they would be red door, or green door, or purple, orange or blue.

And then…

They were in.

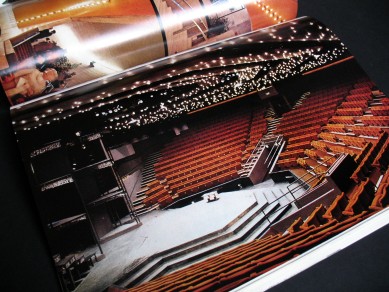

The auditorium itself.

The ceiling: a dense milky way of tiny lights, as compelling as the sky at night. One thousands seats, flipped up and waiting for occupation. Across the rear wall there were boxes scooped out of the concrete – a neat architectural trick that created shadows and mystery on what could have been an otherwise unforgiving expanse. And down at the bottom of the auditorium’s bowl was the stage – half a plywood octagon ringed by shallow steps. It was open and plain and seemed within reach of almost everyone; like a lolling tongue, it probed towards the audience. Seldom could a thousand-seat theatre ever have seemed so intimate.

But the event they witnessed that night was a curious affair; it mixed improvising school children with a little bit of Chekhov (Swan Song performed by Ian McKellen and Edward Petherbridge) and rounded off with a music hall sequence chaired by Douglas Campbell, an actor who had worked with Tyrone Guthrie, even succeeding him as director of the theatre in Minneapolis. And when the evening was over, did the massed crowds of councillors and dignitaries and Playhouse-old-faithfuls understand what the thrust stage could do? Or perhaps did they not want to know? Had the move from Townhead Street to Arundel Gate in fact been an impossible journey?

Some liked what they saw of course, and some didn’t – just like anything. But too many took an ideological position against the Crucible rather than simply deciding that the evening wasn’t for them: it wasn’t a proper theatre, it wasn’t what Sheffield wanted, it wouldn’t make money, it would never be full, it wouldn’t, it couldn’t, it hadn’t, it wasn’t…

And because there was no Guthrie, there was no House of Atreus to follow. Instead, there was Colin George’s production of Peer Gynt, another tricky play with which to fill a thousand brand new seats. What should have been a period of optimism and excitement became something rather less positive as prejudices were confirmed and the city council became nervous, with even its leader, Sir Ron Ironmonger, declaring:

“…within reason, it should offer something for the intellectuals, but basically, it is to entertain the Sheffield public – and this should never be forgotten.”

By any measure, it was a tough beginning. Having built an auditorium that seated a thousand – which to this day remains huge for a regional producing house – the question now was how could it be filled? And the answer was… well, time would tell. It would never be easy, and the shock of the new was clearly severe, but as Tyrone Guthrie had said, “novelty is a curable disease,” and, as it turned out, Sheffield simply got used to the Crucible.

But how that happened is another story, not one for the here and now. And anyway, who’s that guy on the stage…?

—

I walk towards the centre of the arena and turn to face the empty seats, an act that demands a swivel of sorts because the rows embrace me to the right and to the left. At the edge of the stage there is a slight drop to the front row, then beyond that, the auditorium steps steeply upwards away from me, and I can sense how close the audience must seem to an actor who might be standing right here.

“We built what I regard as one of the best theatres in the world, for the playwright, the actor and the audience,” wrote Colin George on the Crucible’s 21st anniversary in 1992. “From the back row of a house seating a thousand you can see the actor’s eye.”

I squint a little as I gaze out at the non-existent crowd, and I can see the eyes of a boy, a five-year-old boy, sitting with his parents and sister. He is watching Pinocchio; it is Christmas 1972. He’s never been in a theatre before, so while the experience itself feels strange, it isn’t the shape of the stage that makes it so. He knows no different. And he likes what he sees.

He appears again in different parts of the house, ageing a little each time – hair longer, hair shorter, face chubby, now thinner – but you can tell that it’s him; he’s familiar. He sees Christmas shows mainly: The Golden Horse Shoe; Jack and the Beanstalk; Cinderella; The Wizard of Oz.

And he’s here on January 1st 1979 with his mum, dad and grandparents – for a pantomimic retread of the melodrama Maria Marten – when the performers reveal that somewhere in the house there is a ‘lucky seat’. “And tonight’s lucky seat is E35!” they declare, and there’s a rumbling around the bowl as kids jump to their feet and dive under the upholstery to see if it’s their turn to shine, but the boy… he doesn’t move; he refuses to believe it could be him.

But there’s a nudging in his ribs from his dad, and a light prickle of cold seems to encroach across his back as he turns this way and that and he realises, with horror, that everyone is waiting for him. Because he is on E35.

“How unlucky,” he thinks as he’s called to the stage; he refuses to move, and begs his sister to go in his stead. But she clamps herself into her allotted seat, and the audience grows restless, so with a hollow in his stomach he finally drags himself down the centre aisle and takes the hand of the man – the actor – on stage.

In just one step, he moves between worlds: from the audience into make believe. And now he’s facing his crowd, blinded by the limelight and feeling more than a little sick. He answers the actor’s questions – how old?; which school?; is this fun? – then conducts the audience in a nonsense song, accepts a huge box of Thornton’s chocolates, and not a moment too soon, he vanishes back into the darkness with a full Crucible round of applause ringing in his ears.

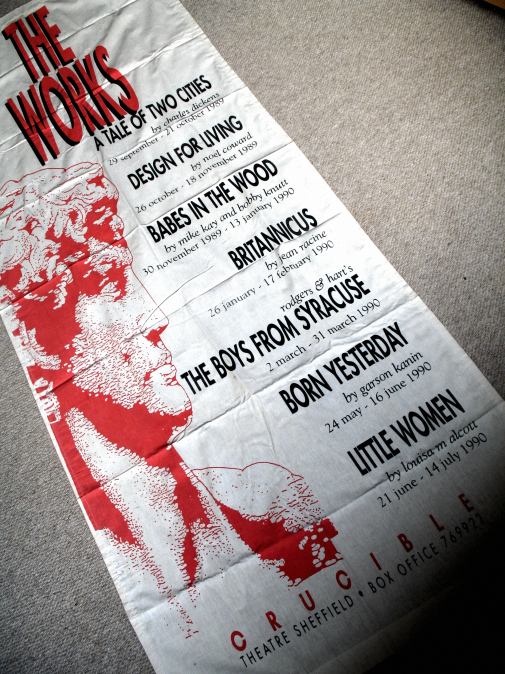

You’d think after that he might never return, and indeed, as he turns into a teenager the visits become fewer and fewer… but then come school trips, the Hamlets and Macbeths, and eventually it occurs to him that he could actually come here on his own. So he does: for Brecht, for Miller, for Rodgers and Hart; for all kinds of things that he books on a whim.

He sees the Crucible stage as a shifting and restless place: as the Forest of Arden or the Ranevskaya estate, as the California dust bowl or as Willy Loman’s final resting place. He wonders at the labours that go into its eternal demolition and rebuilding; and when he sets eyes on its newly imagined form yet again, his breath is often taken away.

What he doesn’t quite notice is that the Crucible is a little different now; its stage has made a break with its past. Whereas once it was a platform built for the classics – literally a platform; a raised promontory with steps and a moat – it is now a single vast expanse that reaches from the rear stage right up to the wiggling toes of the front row. And the laddered towers at the back – which had been designed to offer just the suggestion of an atmosphere, or an abstraction of a time and place – have now vanished, and in their place have come… well, anything that a designer can realistically conceive. It is an evolution of the thrust stage vision, and it is not what Tanya Moiseiwitsch had in mind.

When the Architectural Review warned in 1972 that “these theatres have a certain visual aridity,” they meant that the Guthrie-derived stages lacked the crowd-pleasing visual touches that a breathtaking set could bestow. They were built for intensity, for passion, for looking into an actor’s eye, but they were not the place for grand designs. But it’s a description that this boy – still a boy?; perhaps not – wouldn’t recognise, because to him, the Crucible means spectacle and visual exhilaration. He loves the complete transformation that occurs here, the way the stage is rebuilt every time. If he thought about it he might realise that it’s more like architecture than stage design: it’s as though the theatre changed its nature in order to make Sheffield – and him – love it more.

He moves away from the city for a time, and the building becomes a talisman reminding him of home. He loves its greyness, its harshness, its splashes of colour; he loves the way it renders drama inescapably its own. Its stage is not flexible – it’s not a bit of this and that – and it imposes itself; it demands that the players pay attention. For touring shows it’s far from perfect; visiting productions must be bent out of shape to accommodate the stage when usually it would be the other way round. But for those shows that are birthed here, that live and die on the Crucible’s thrust… please excuse him; he’s got something in his eye. You see, he is surprised by this now that he thinks of it; he’s embarrassed by how much he loves it. Because… it’s just a theatre after all; just somewhere to watch a play.

But as that constellation of tiny bulbs begins to dim, and the chatter of a full house dies away, and the lights come up on Orsino’s palace, or the Kit Kat Club, or Neverland, he thinks he would give anything to actually be part of it, to be free to wander its passages and hidden corners, and maybe to explore the hidden world that lies beneath its incredible stage. Perhaps one day, he thinks, he could even work here…

—

I become aware that I have a job to do, and it’s time to move on. I scuttle back down the tunnel stage left, walk quickly now through the understage gloom and emerge back into the corridor’s light. Up the stairs I go, passing the stage door and the switchboard where I meet some lads from the bar talking football, then I rush through the scene dock and round the back of the Studio, still checking fire escapes as I go.

The Studio’s stage manager is arranging props and she grunts a ‘hello’ as I pass, but I can’t stop; I’m running late. I throw open the pass door that leads to the Studio foyer, I check the toilets, and I walk past the box office where one day I’ll get a job; and I’ll meet my future wife there; and life will head off somewhere else. But for now I trot past quickly – the staff in there seldom pass a greeting – and I head up the main staircase to the coffee shop where there are more toilets to be inspected.

I’m almost running now as I scan every cubicle and head back to the main foyer; but on the stairs I pass Clare Venables and she stops to greet me and shake me by the hand. I’m a little awed, I admit; she’s the Artistic Director, and has been for the past eight years. Her brand of theatre is stylish and radical; it attracts the national press and she’s built a great reputation – both for herself and for the theatre we are in. This will be her final season in Sheffield; in 1990 she will leave, just as the freshly renovated Victorian Lyceum across the road is reopened to great acclaim, and suddenly what was once the new kid on the Norfolk Street block – this crucible; this extraordinary relic of the 1970s – will become the old trouper fighting for attention as the follow-spot sheds its light elsewhere. Sheffield will finally regain its grand proscenium arch, and things will get difficult once more for the Crucible; and the arguments that many thought had been won will begin all over again.

There are those who think that with the opening of the Lyceum, it will be the Crucible’s turn to share some indignity; by ditching its pretensions and becoming a snooker hall perhaps?

Ah, snooker. Well… that’s a story for another potted history – but not this one.

Clare hurries on, the stresses of funding and board meetings lending a hunch to her gait. I reach the main foyer and I can see that the usherettes are already hovering at the end of the bar, so I pull my keys from my pocket and unlock the heavy chain around red door. They gather around me in their maroon cardigans and nylon skirts, exuding pheromones as they file into the auditorium one by one, ready for their pre-show briefing from the duty manager. Some of us flirt a little, and blush, and there’s giggling; I tangle myself up in possibilities as they pass. Enjoying this warmth, I follow them through the doors and stand nonchalantly to one side as they squabble over where to sit. I pretend that I was passing through anyway, but of course, this historic space is a cul-de-sac; it’s not supposed to be a part of my rounds. I’m going nowhere, and when the manager arrives I will be hurried on my way. But for now, this is about as good as life gets; with these people – these Kerrys and Nickys and Sarahs and Joannes – beneath these lights, looking down from on high at the extraordinary, magnificent Crucible stage.

—

Interviewed by The Observer newspaper in November 2009, the theatre director Jonathan Church remarked:

“Theatre is never about buildings, it is always about the work – you forget that at your peril.”

Instinctively, you feel that he is right; what happens on the stage must be more important than the building in which it occurs… mustn’t it?

Well yes, to a point. At any particular moment, it is the work that matters; the way the company interacts to generate theatre that can hopefully live long in the memory. But time passes; actors and directors move on; a theatre becomes a repository of accumulated experiences collected by the community to whom the building belongs. In an ephemeral medium, the shows they see – the dramas, the musicals, the comedies and tragedies – all evaporate, leaving nothing but a residual energy. And it is in the physical fabric of the building that those shifting memories become enmeshed, and in this way it is the building that becomes the theatre; less so the work.

The thrust stage at the Crucible is not the only auditorium in the place. There is a small studio theatre too, the archetypal ‘black box’ performance space with its manoeuvrable banks of seating that can be configured into any intimate set-up. I’ve seen such interesting stuff there: exquisite jewels of world drama; two-handers and monologues; and even – in unfussy rehearsed readings that nevertheless were enough to almost stop my heart – some work of my own. But the Crucible Studio, for all the opportunity it affords the director and performer, does not thrill me at the very mention of its name; and that’s because there are many black box studios in this country and beyond; and one is very much like another. It does little to add to the Crucible’s personality even while being integral to its theatrical health. So even though the work is generally good, the Studio is only a minor ingredient in the Crucible’s irresistible recipe.

“Theatre is never about buildings” is a theatre professional’s point of view. But those professionals are like the players and managers at a football club, who care about the performance of the moment – the last game, the next game, and at a pinch the one after that. Because next year they’ll have gone, moved on, to declare their passion for someone else, another team entirely. But for the fans, it’s different. For them, the club isn’t just the players who’ll pull on the shirt next Saturday. It’s the first match they saw, the first song they sang, the first time they saw a fight there. It’s the broken turnstile behind the Kop where kids used to duck in for free. It’s the hat-tricks, the penalties, the everlasting nil nil draws. It’s tea slurped, banter swapped, pies scoffed.

Likewise, a civic theatre, once built, becomes much more than just a vessel for the work. For a start, it is a statement of ambition, the product of an argument; the physical manifestation of hours and hours of talk between councillors and luvvies and people with money, between those wearing suits and those in corduroy. Did those with ambition win the day? Or did the book balancers convince them to be ‘realistic’? You’ll find the answer right there in the building itself, because that’s the last word of the debate.

And it’s a landmark, of course. Whether impressive, mediocre or best ignored, it’s as much a part of the city as the cathedral, the shops, the town hall. Time tells whether it’s a good part or bad, but once there, it’s there; and you’re stuck with it.

And then, and then… it’s kids at the panto, first nights and first dates. It’s actors cramming lines and noisy lads in the bar. It’s usherettes passing gossip, a double booking, bags of fudge. It’s late comers, it’s intervals, it’s soliloquies gone wrong. Here’s a school party, there’s a drunk. Piles of leaflets, blocked toilets, stifled sniggering, a perfect hush. And the coughing, always coughing.

The Crucible Theatre, then, is all these things and more. But at the core of the experience is that ridiculous stage: a great folly perhaps; a white elephant; an inglorious tram shed. It is a product of its moment, and had that moment passed without action, the place would certainly never have been built. But it’s here, and it’s Sheffield’s, and it does something epic to the words on a page. It’s the bravest gesture of the city’s post-war reconstruction, and while so many other bunker-like structures of that era are now saying their farewells, at the Crucible, the house lights are dimming again. And as always, that means something special is about to begin.

—

I slam my locker shut; the show has come down; my waistcoat and bow tie are packed away. Zipping up my jacket I head down the back stairs – past the accounts office where I pause to cram the programme money into the night safe. At stage door there’s a hubbub as disparate breeds intermingle: bar staff with stage crew with actors freshly scrubbed – the performers always fizzing with that effervescent manner they possess. Some wait for taxis, others just pass time; and June on the switchboard – who has been here since the Crucible first opened – casts glances and raises eyebrows and deals with them all one by one.

It’s a friendly scene; irresistible in a way. And though I make to step outside, I hang back a little, just wanting to remain part of it some time longer. But I can’t stay forever; the evening’s done; so I push at the doors and walk down onto Norfolk Street, and as I glance back there’s a warm light in the stage door window, but no one looking out.

I realise as I slope off for the bus that I have a piece of paper in my hand. It’s my Crucible seating plan, the one I was given the first day I arrived. It’s tatty now through constant use; it gets folded and unfolded several times a night as I direct customers to their seats and help them navigate their way around the building.

But I don’t need it now because I’m on my way home. So I fold it into squares and thrust it back into the depths of my pocket as the theatre grows more distant behind me.

The Crucible is now run in partnership with the adjacent Lyceum Theatre. The managing body is called Sheffield Theatres, and with three distinctly different auditoria – a Victorian proscenium arch, a 1970s thrust stage and a flexible ‘black box’ studio – it has become one of the major centres of theatrical production in the UK. In January 2010, shortly after I wrote this article, the Crucible reopened after a two-year £15 million renovation project. The front-of-house areas were enlarged with the aid of a rather clumsy extension, but the Tanya Moiseiwitsch-designed auditorium is better than ever. And with a vivid new foyer carpet based on the 1971 original, the Crucible’s future continues to look bright.

If you have any comments to make about the Crucible Theatre in general or this article in particular, don’t hesitate to contact me via the Contact page on this website.

More writing about theatre on Noise Heat Power:

Dedicated to discomfort – A personal history of the Liverpool Everyman

The Crucible method – Forty years of the Sheffield Crucible

For the Lyceum with love – A brief history of the Sheffield Lyceum

Text © Damon Fairclough 2010

Images © Damon Fairclough 2010

Share this article

Follow me